Severini Gino

Severini, Gino. – Pittore (Cortona 1883 – Parigi 1966). A Roma dal 1899, conobbe U. Boccioni e G. Balla che lo introdusse alla tecnica divisionista. Stabilitosi nel 1906 a Parigi (dove trascorse, con intervalli, la maggior parte della sua vita), S. entrò in contatto con i circoli dell’avanguardia artistica e letteraria legandosi, in particolare, a P. Picasso, A. Modigliani, M. Jacob e P. Fort.

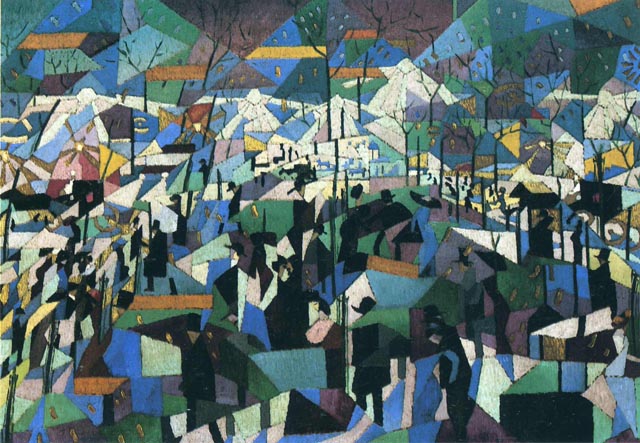

Orientatosi inizialmente allo studio di G. Seurat in paesaggi e vedute di Parigi di grande sensibilità cromatica, si volse poi, sollecitato dalle istanze futuriste e dalla poetica unanimista di J. Romains, verso soluzioni formali che tendono a rendere il senso del movimento cosmico (Danza del Pan Pan al Monico, 1909-11; dispersa durante la prima guerra mondiale, l’opera fu ridipinta da S. nel 1960 in base a documenti fotografici, Parigi, Musée national d’art moderne).

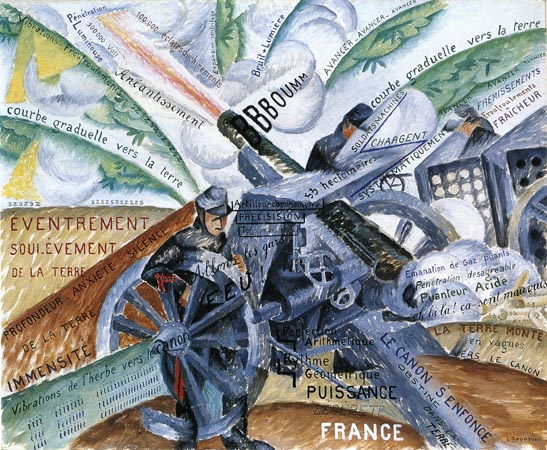

Tra i firmatarî del primo Manifesto della pittura futurista (1910), S. svolse un importante ruolo di collegamento tra l’ambiente parigino e il gruppo futurista (nel 1912 collaborò con F. Fénéon all’allestimento della mostra Les peintres futuristes italiens). Dopo un soggiorno in Italia (1913-14), tornato a Parigi, S. portò avanti, accanto a dipinti che interpretano in modi cubo-futuristi la guerra (Cannone in azione, 1914-15, Francoforte, Städelschen Kunstinstitut), una serie di opere ispirate all’orfismo (Mare=Ballerina, 1913-14, Venezia, Fondazione Guggenheim) e al cubismo sintetico (Zingaro che suona la fisarmonica, 1919, Milano, Galleria d’arte moderna). Nel 1921 pubblicò il saggio Du cubisme au classicisme che sancì la sua adesione a una figuratività piena e cristallina, preannunciata da opere quali Maternità (1916, Cortona, Museo dell’Accademia etrusca).

Con un intenso lavoro di elaborazione teorica, in sintonia con le posizioni espresse dal gruppo di Valori plastici, al quale aveva aderito nel 1919, S. giunse alla definizione di calibrati ritmi compositivi nei quali temi desunti dalla commedia dell’arte, ritratti e nature morte con frammenti dell’antico, appaiono immersi in atmosfere metafisiche di luce mediterranea. Dagli anni Venti, segnati anche da una crisi religiosa culminata nel 1923 con la piena adesione al cattolicesimo, S. tese ad abbandonare la pittura di cavalletto per dedicarsi alla decorazione murale, trattando con grande talento decorativo l’affresco e il mosaico (cicli decorativi per il castello di Montefugoni, Firenze, 1922; per la chiesa di Semsales, Friburgo, 1924-26; per la chiesa di Notre-Dame du Valentin di Losanna e per il palazzo della Triennale di Milano, nel 1933; per l’Università di Padova e per il Foro Mussolini a Roma, nel 1937). Stabilitosi dal 1946 a Meudon, S. tornò all’astrazione geometrica, recuperando con grande equilibrio decorativo tematiche e modi d’ispirazione cubista (decorazioni per il Palazzo dei congressi a Roma, 1953). Oltre a scritti sull’arte contemporanea, pubblicò i volumi autobiografici Tutta la vita di un pittore (1946) e Temps de l’effort moderne. La vita di un pittore (post., 1968).

(English)

Life

Gino Severini (7 April 1883 – 26 February 1966) was an Italian painter and a leading member of the Futurist movement. For much of his life he divided his time between Paris and Rome. He was associated with neo-classicism and the “return to order” in the decade after the First World War. During his career he worked in a variety of media, including mosaic and fresco. He showed his work at major exhibitions, including the Rome Quadrennial, and won art prizes from major institutions.

Severini was born into a poor family in Cortona, Italy. His father was a junior court official and his mother a dressmaker. He studied at the Scuola Tecnica in Cortona until the age of fifteen, when he was expelled from the entire Italian school system for the theft of exam papers. For a while he worked with his father; then in 1899 he moved to Rome with his mother. It was there that he first showed a serious interest in art, painting in his spare time while working as a shipping clerk. With the help of a patron of Cortonese origins he attended art classes, enrolling in the free school for nude studies (an annex of the Rome Fine Art Institute) and a private academy. His formal art education ended after two years when his patron stopped his allowance, declaring, “I absolutely do not understand your lack of order.”

In 1900 he met the painter Umberto Boccioni. Together they visited the studio of Giacomo Balla, where they were introduced to the technique of Divisionism, painting with adjacent rather than mixed colors and breaking the painted surface into a field of stippled dots and stripes. The ideas of Divisionism had a great influence on Severini’s early work and on Futurist painting from 1910 to 1911.

Severini settled in Paris in November 1906. The move was momentous for him. He said later, “The cities to which I feel most strongly bound are Cortona and Paris: I was born physically in the first, intellectually and spiritually in the second.” He lived in Montmartre and dedicated himself to painting. There he met most of the rising artists of the period, befriending Amedeo Modigliani and occupying a studio next to those of Raoul Dufy, Georges Braque and Suzanne Valadon. He knew most of the Parisian avant-garde, including Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso, Lugné-Poe and his theatrical circle, the poets Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Fort, and Max Jacob, and author Jules Romains. The sale of his work did not provide enough to live on and he depended on the generosity of patrons.

In the 1940s Severini’s style became semi-abstract. In the 1950s he returned to his Futurist subjects: dancers, light and movement. He executed commissions for the church of Saint-Pierre in Freiburg and inaugurated the Conségna delle Chiavi (“Delivery of the Keys”) mosaic. His mosaics were shown at the Cahiers d’Art gallery in Paris and he participated in a conference on the history of mosaic at Ravenna. He received commissions to decorate the offices of KLM in Rome and Alitalia in Paris and took part in the exhibition The Futurists, Balla – Severini 1912–1918 at the Rose Fried Gallery in New York. In Rome he reconstructed his Pan Pan Dance mosaic, which had been destroyed in the war. He was awarded the Premio Nazionale di Pittura of the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, exhibited at the 9th Rome Quadrennal and was given a solo exhibition at the Accademia di San Luca.

Throughout his career he published important theoretical essays and books on art. In 1946 he published an autobiography, The Life of a Painter.

Severini died in Paris on 26 February 1966, aged 82. He was buried at Cortona.

Futurism

He was invited by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Boccioni to join the Futurist movement and was a co-signatory, with Balla, Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, and Luigi Russolo, of the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters in February 1910 and the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting in April the same year. He was an important link between artists in France and Italy and came into contact with Cubism before his Futurist colleagues. Following a visit to Paris in 1911, the Italian Futurists adopted a sort of Cubism, which gave them a means of analysing energy in paintings and expressing dynamism. Severini helped to organize the first Futurist exhibition outside Italy at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, in February 1912 and participated in subsequent Futurist shows in Europe and the United States. In 1913, he had solo exhibitions at the Marlborough Gallery, London, and Der Sturm, Berlin.

In his autobiography, written many years later, he records that the Futurists were pleased with the response to the exhibition at Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, but that influential critics, notably Apollinaire, mocked them for their pretentions, their ignorance of the main currents of modern art and their provincialism. Severini later came to agree with Apollinaire.

Severini was less attracted to the subject of the machine than his fellow Futurists and frequently chose the form of the dancer to express Futurist theories of dynamism in art. He was particularly adept at rendering lively urban scenes, for example in Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin (1912) and The Boulevard (1913). During the First World War he produced some of the finest Futurist war art, notably his Italian Lancers at a Gallop (1915) and Armoured Train (1915).